WRITING ABOUT OPPRESSION AS AMERICA FALLS

- Cully Perlman

- Jan 20

- 7 min read

All my life, or at least my writing life, has been focused on power and the power structures that oppress people in some form or fashion. I have written about the power structures created by org charts at companies, primarily from the experiences I’ve had working at some of the largest advertising/digital agencies for seventeen, which included working with clients like Microsoft, Home Depot, the U.S. Army, the U.S. Air Force, Verizon Wireless, PCL Construction, SPX Technologies, UTC Aerospace Systems, but also companies in other industries, including higher education, real estate, technology/SaaS companies, and even in the restaurant/hospitality industries. Mostly, my focus is on politics. While my novels on political issues have not been published (they’re still in various stages of revision, but also being queried), it’s my main focus. But there’s a trick, in my experience, to writing about politics from a fictional perspective. That trick: either knowing the political arena in which you’re writing extremely well, meaning you have shadowed a politician or read biographies and other fictive accounts of some aspect of politics, or by approaching the subject matter from a side angle, meaning not head on.

As I write this, Renee Nicole Good, a 37-year-old mother of three, and a recent transplant to Minnesota, was murdered by an ICE agent, and I believe it's important to listen to Lawrence O'Donnell take on Renee Good's murder. I understand the word “murder” is inflammatory. It’s meant to be. I have watched the video of the murder, and unlike what the Trump administration is trying to spin, it was murder, plain and simple. ICE agents are a threat to this country in much the same way that Trump and his entire administration are a threat to this country. I won’t get into his dismissal of political norms and rules (like his regime change and taking over Venezuela and its oil, or his desire to “buy” or “take away” Greenland, or the brutality of January 6th and Republicans whitewashing and lying about what really happened that day). I won’t, because my usage of the terms I just used makes the point I’m trying to make, which is this: It isn’t an easy task, writing about politics without sounding preachy. You may believe in all the things I just wrote; you may believe everything I just wrote is hearsay, or “fake news,” or hyperbole. Either way is fine. I have my beliefs; you have yours. But when reading fiction, no one wants to be preached to. What they want is a story. And if you’re going to be successful in fiction, a story is what you must produce.

Over my writing career, I have written both forms of fiction, i.e., the kind where I did a lot of research, but I have also written the kind of fiction where, for lack of a better way to put it, I preached to my prospective readers. I’ve been writing for a long time. I throw away the writing where I’m being preachy, for that, as a writer of fiction, is not my job. Again, my job is to tell a story, and to tell it well. Preaching my beliefs to readers is not fiction. Preaching (and we can argue all day about this) is a form of nonfiction. I may influence or make commentary or introduce themes into my fiction that communicates my beliefs clearly and, hopefully, succinctly. But readers of fiction want a plot (or most do, even if they don’t know it). Readers of fiction want to be entertained. Readers of fiction don’t want to hear your political views directly thrown at them any more than readers of nonfiction want to have you write lies or bend the truth. They are two different forms of writing, and I believe they should be as clearly delineated as possible. Yes, conclusions in nonfiction are often based on the author’s hypothesis given the information at their disposal. But that’s not fiction, it is, unfortunately, what they must do in order to give the reader what they want: a conclusion that makes some sort of sense.

Here are Chekhov’s rules for writing fiction*:

Absence of lengthy verbiage: Avoid overly detailed political, social, or economic descriptions unless essential to the story.

Total objectivity: Present facts and characters without imposing your own judgments; let the reader draw conclusions.

Truthful descriptions: Be accurate and realistic in portraying people and objects.

Extreme brevity: Say only what's necessary; every word should count.

Audacity and originality: Dare to be new; avoid clichés and stereotypes.

Compassion: Show empathy for your characters, even when depicting their flaws or suffering.

Chekhov's Gun (Principle of Economy)

Core Idea: Every element in a story must be necessary and serve a purpose (plot, character, theme).

Application: "Remove everything that has no relevance to the story." If you introduce a detail, like a rifle on the wall, it must be used later. If it doesn't get fired, cut it.

Purpose: Prevents misleading the reader with unnecessary details and builds narrative efficiency and tension.

And here are 5 tips from Writer’s Digest on writing political fiction:

Figure out what your book is (really) about

Be clear about what purpose politics will serve in your book

You don’t have to chase the headlines (unless you really want to)

Make your characters and events as different from the news as possible

Accept that you’re not going to please everyone

Chekov’s rules are more about writing fiction in general. Writer’s Digest’s rules are more about how to write about politics without annoying the reader or rehashing the day’s political events. There’s room for both writing, but they’re different—one is fiction, and the other is nonfiction disguised as fiction. I’d argue there isn’t room for the latter, as readers don’t necessarily pick up a novel to have the news told to them as if it were made up. I’ve read novels like that, and it takes me about three sentences to realize the writer has neither written fiction nor nonfiction but a bastardization of both, which just doesn’t work. In my opinion, ever.

I’ve recently completed a first draft of a novel that deals with a man falling into conspiracy theories after losing his job and his career. Now, it would be easy to throw in Pizzagate, and QAnon conspiracies, and their deep state theories, and every and any conspiracy Trump, Stephen Miller, Kristi Noem, Jim Jordan, and the rest of Trump’s cronies consume and then spit out into the world as fact. But I didn’t. The conspiracy theories my protagonist consumes are not explicitly explained to the reader. I do not go into detail about what my hero believes, or what he does about them, nor does he provide information dumps to either his wife or anyone else in the novel. I tell a story. My hero wants something, goes after it, faces hurdles, overcomes those hurdles or doesn’t, reaches a climax, and then I go into the falling action, resolution and denouement. No, what I do is hint at what the conspiracies are. I show through my hero’s reaction to what he’s reading through the actions he takes or wishes he had the courage to take. I show through his anger that he’s seeking out supplemental issues to add to the grievances he already possesses due to the loss of his job and the loss of the control he believed he’d earned over a lifetime of hard work. Am I writing about politics by him paying attention to the propaganda he has chosen to fill his days with while searching for jobs? You bet. But I’m not ramming it down my readers’ throats. All I’m doing is throwing out subtle signifiers that readers can then run with in their imaginations.

So, you ask, how do you do that? The answer is simple: I do what I’ve outline above, but I also read the political novels of the past that have handled the subject appropriately in fiction. I listed a number of novels out there that I believe worthy of reading if you want to learn how to write about politics in your fiction. The post was titled “Politics in Fiction: The Best Political Novels to Read & More.” You can read that post by clicking the link. A couple of other posts on the topic: “Political Fiction and the Novels That Stand the Test of Time” and “Do Political Novels Make a Difference in American Culture?” Take a read of them and let me know what you think in the comments.

IT'S a TOUCHY SUBJECT, WRITING ABOUT OPPRESSION AS AMERICA FALLS

Now, I get that politics is a touchy subject. And as mentioned, I am writing fiction, which requires that I do not preach but rather provide readers with fiction they find interesting, which means the rules of fiction apply just as they would in genre fiction or any type of fiction in general. Fiction should entertain. Fiction should follow certain rules, but the rules may be broken if you know what you’re doing. But fiction should, during the revision process, be analyzed objectively, not by emotion alone. You can write down whatever you want, but you should know the difference between what you should keep in your novel, and what darlings you must kill.

The key to writing political novels, or fantasy, or genre fiction or whatever type of fiction you write, is this: write the book you want to read. Obviously, I have my own political and other opinions, just like you and every other writer out there does. That’s a good thing. We, as a reading and writing community, benefit by diverse opinions and diverse writing and communication. I’ve posted about politics before and people feel the need to comment negatively. That’s their prerogative. I don’t mind that. I won’t allow attacks or cursing, but I do encourage debate. But if you want to write a novel about politics, remember the golden rule: fiction is made up, no matter how much truth is in it, and nonfiction is fact (or, at least, the closest to fact we can get). Know the difference. And understand the difference between preaching in your fiction and telling a story. If not for your sake, at least for your readers.

Writing about oppression as America falls is not going to be an easy thing for you as a writer to do. It will require stepping back from what you've written and asking yourself, as a reader, if you've done justice to what you're trying to achieve from a fiction perspective. But you can do it. And I think now is the time to try.

Cully Perlman is author of a novel, THE LOSSES. He can be reached at Cully@novelmasterclass.com

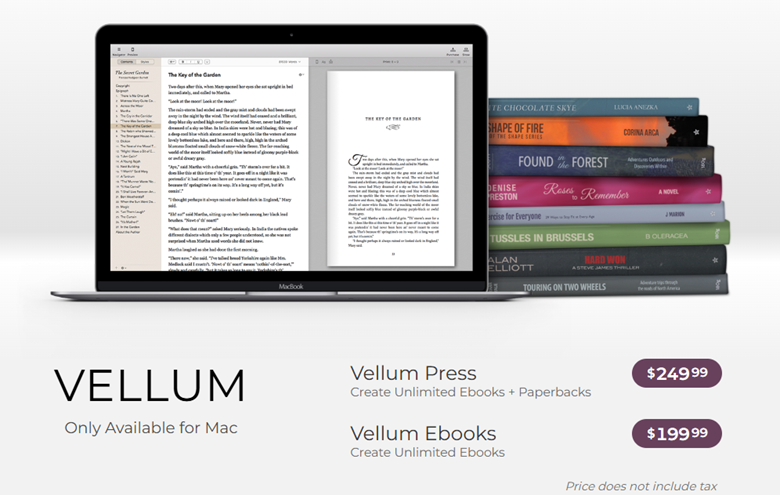

Any commissions from affiliate links pay for hosting and platform costs so as to keep this blog free to you, our readers.

*All definitions are quoted directly from Google’s AI Overview.

Comments